IP-6-2016 (August 2016)

Author: Bruce Baker and Mike Krause

Executive Summary:

This paper examines the empty promises and untold costs of Urban Renewal Areas (URAs) and the use of Tax Increment Financing (TIF) in URAs in Colorado. The paper will show that:

- Urban renewal authority and discretion is being routinely abused, in direct violation of the legislative intent of the law.

- URAs/TIF has failed to bring economic benefits commensurate with the costs.

- The value that URAs give in generating economic development is overstated.

- URAs have been unable to override the profound effect of the general business cycle.

- URAs have been unable to ignite economic development in the URA or in adjacent areas.

- TIF incentives justified with “but for” arguments have merely raised the expectation and demand by developers for public subsidies.

- The unfairness in the present system is revealed by the fact that 1/2 of the state backfill education dollars go to Denver, which teaches 1/10th of the state’s students.

- URAs and TIF have been commandeered by governments to advance the pet projects of connected insiders and social planners.

- Clear abuses are occurring and that state resources are being disproportionately given to the richest municipalities in the state.

- The legislature should end this routinely abused practice altogether.

What is a TIF?

Tax Increment Financing is a mechanism whereby the increase in taxes collected on and at a specific site, caused by the re-invention of that site, may be used to repay bonds that fronted the costs for the re-invention of the site. The money raised by the bonds may finance projects such as assembling properties, building roads, replacing water and sewer systems and other infrastructure, replatting the site, legal costs, etc.

In theory, the costs of re-inventing the site will be paid by the new residents/owners of the site and amortized over 25 years. The success of the theory depends on the re-invented site requiring the same or fewer government services than the old site required.

An example is the calculation of the sales tax increment at the Orchard Mall at I-25 and 144th Ave in Westminster.

Tax collections for 2015 were $6,039,397. Next subtract the collections that existed before the URA was formed, which is $0 (a vacant field did not collect any sales tax). The tax increment is $6,039,397

Another example is the property tax increment at the Target store at 144th Ave and Huron in Westminster.

The 2012 property taxes are $396,903. Because the parcel of land was split off from a larger tax parcel that existed before the URA was formed, the calculated tax was estimated to be $8,400. The tax increment on the Target store is $388,503 (the total site increment is steadily increasing and moving beyond $6 million per year).

Both of these revenue sources were pledged to repay the approximately $70 million in bonds that re-invented the North Huron Urban Renewal Area.

Introduction

Robert K. Merton in his 1936 article “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action” delineates reasons why social planning does not always yield the results the makers of the policies had in mind.1 A failure to yield the planned results is exactly what has happened with Colorado’s Urban Renewal Areas (URAs) and their current financing mechanism, Tax Increment Financing (TIF).

The challenge in Colorado is to convince lawmakers that we have been fooled into believing that URAs are defeating an ongoing menace to the people of Colorado and that the significant costs of these programs have been fairly shared.

It is important to remember that the citizens grant awesome power to government. American society is the beneficiary of a culture which fully believes and endorses that lawful power comes from the consent of the governed. For the few that break the law, enforcement is applied in measured amounts. Not only is enforcement applied in measured amounts, but the necessity of law has a direct correlation to the amount of power given to the government. For example, the government, with clear and convincing reasons, has the power to immediately confine a person that could spread drug-resistant tuberculosis to the public. When contrasted with a person that will not control the weeds on his property, it will be years before the government can exercise any power to force that person to do anything. There are very few incidents where government must exercise the maximum force of their power.

Remembering this range of government power is vital in any discussion regarding Urban Renewal law. The Legislative Declaration in Colorado’s Urban Renewal law (CRS 31-25-102) is very clear that the reasons for granting sweeping power to URAs is because there exist “slum and blighted areas” in municipalities that constitute a “serious and growing menace” to the public health, safety, morals, and welfare. That, unaddressed, these areas would contribute substantially to “the spread of disease and crime.” That municipalities must not continue to be endangered by areas which are “the focal centers of disease” and “promote juvenile delinquency,” and which consume an “excessive proportion” of government revenues. If urban renewal areas do not meet the legislative intent of the URA laws, municipalities are misusing the power granted to them by the Legislature. (For the complete text of the legislative declaration, see appendix A).

The concern of municipalities for all areas in their towns is necessary and should be expected, but URAs are not the only tools municipalities have at their disposal. There are many tools available to address the problem of struggling areas; be they commercial, residential, or public. Besides General Improvement Districts, Metropolitan Districts, Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), and city sponsored incentives and partnerships, there are Downtown Development Areas (DDAs), as cited in CRS 31-25-801. This range of tools available to municipalities shows the government arsenal of measured responses. The difference in the amount of power made available by Colorado between URAs and BIDs shows the same, thoughtful distribution of power in relation to the threat of the problem as shown between contagious diseases to weeds. The enormous power of URAs presents a seductive temptation to municipalities when compared to the weaker, more-work-on-their-part alternatives.

Because it is so easy for municipalities to use legislative discretion, and so difficult for any other government to challenge, municipalities can declare nearly any area as “blighted”.2 Municipalities have been lulled into seeing URAs as an ordinary exercise of their power. Municipalities are using a tool meant only for serious threats to the public as a tool for gaining a competitive advantage in economic development. Which, essentially, is a way to financially reward development partners and a method to force the public into a future desired by government planners.

Moreover, the use of TIF forces Colorado taxpayers, who live outside the URAs to help pay for this ongoing abuse of the law.

TIF is a diversion or reassignment of tax revenues to repay bonds that are issued to subsidize a government desired development on a specific site. The money that funds TIF, the increment, is the difference between the taxes collected before development on a specific URA site the taxes collected after development.

Any examination of URAs and TIF should logically begin by asking the hard questions. Do URAs fulfill the promises they make? Are the costs of URAs meaningfully understood by the public? Do URAs achieve their stated goals?

LET’S MAKE AN URBAN RENEWAL AUTHORITY (URA)

First: Registered electors petition the governing body (town or city council).

Second: The governing body holds a public hearing.

Third: The governing body passes a resolution that finds:

a: Slum and blighted conditions exist in the defined area.

b: The governing body must take action to address the slum and blight in the interest public health, safety, morals and welfare.

c: It is in the public interest to form a URA and use the State granted powers to combat the slum and blight.

Fourth: Appoint a URA board (which could include members of the governing body themselves).

Fifth: File the appropriate paperwork with the Department of Local Affairs.

Sixth: The authority can then designate urban renewal areas as desired.

Empty Promises

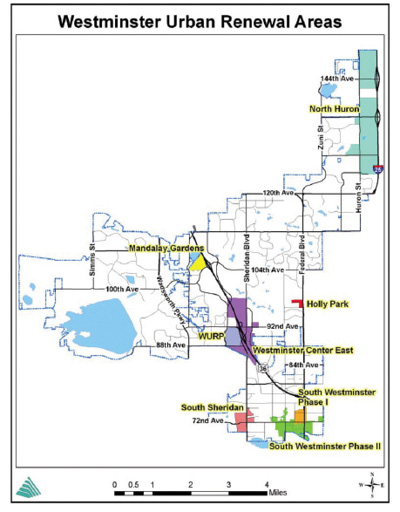

The promises made by URAs have been partially delivered to individual cities that sponsor URAs. There have been disappointments (South Westminster Phase II and Holly Park are two failed URAs in Westminster) but in most cases the municipality has achieved their immediate goals. The longer term goals and promises, however, have fallen flat in many cases. The promises made under urban renewal legislation were not only to the residents within a municipality, but to all Coloradans. Those promises have not been delivered.

Eliminating “Slum and Blight”

The first promise left empty by urban renewal is that URAs and TIF serve both the intent and spirit of the law to eliminate slum and blight. It does not. The Legislative Declaration of CRS 31-25-102 is clearly patterned after the Federal Housing Act of 19493. Both federal and state laws seek to address the problems and threats that come from people living in substandard housing amidst squalid conditions. The use of the words “disease” and “crime” were not used by accident. Diseases and crimes are what make the slums and blighted areas worthy of statewide interest, and warrant the state government enabled response that delegates the power of property tax diversion and condemnation to municipalities. The high level of threat from slum and blight is the reason for a high level of power.

As Colorado Urban Renewal law evolved over the last several decades, an unexpected turn of events happened. Slum and blight have been all but eliminated. The American story in housing, a result of the free market coupled with rise of the standard of living, has eliminated the slums and blighted areas that the Federal Housing Act of 1949 was meant to address by allowing Americans true alternatives to the crowded, controlled choices in cities. The inexpensive, suburban homes of William Levitt, the mortgages of the GI Bill and the FHA, the everyman cars of Henry Ford, and the grade-separated highways of Dwight Eisenhower overcame the economic and distance barriers that kept people trapped in cities.

The transformation did not occur overnight. It took decades. The transformation also did not happen as a continuous forward progress. There were starts and stops. There was waste and corruption. In retrospect, many people question the efficacy of and acknowledge market distortion caused by federal programs.4,5 However, it is undeniable that the housing real estate market in the United States is a working example of the free market, based on millions of willing buyers and sellers setting values and allocating resources to the benefit of society.

The reality of today is that slums, which breed disease and crime, and pose an imminent threat to the state in general, do not exist in Colorado. This should be a cause for celebration. This should mean the slum and blight elimination programs can be ended and those funds can be re-directed to other programs, or returned to taxpayers. Colorado never really had the slums of the big eastern cities, so our problem with slum and blight was not as large as other states. However, anyone wishing to end a lucrative government program must battle the entrenched special interest beneficiaries of the program.

Federal funds had effectively dried up by the 1970s, but no victory over slum and blight was declared. Instead, advocates of government spending and a government planned future switched to Tax Increment Financing (TIF) to fund URAs.

In a review of Colorado URAs, only a handful of properties, using the most inclusive, liberal, and broadest of definitions, would even approach the designation of slum. As for areas that would endanger the State and its municipalities as focal centers of disease, or promote juvenile delinquency and consume an excessive proportion of revenues, there are none. No URA in Colorado has ever been independently identified as a source of disease and crime. The following list of URAs exemplifies the typical Colorado project. Not one of these was an area of “slum and blight,” or disease, or crime.

- North Huron URA: vacant farmland.

- Westminster Urban Renewal Project (WURP): struggling regional mall.

- Holly Park URA, Westminster: partially built bankrupt townhomes.

- South Sheridan URA: assemblage of vacant land.

- Walnut Creek URA: assemblage of several ranchettes.

- South Westminster: struggling commercial property.

- Westminster Center East: commercial properties.

- East 144 and 125 URA: vacant farmland, school district bus facility.

- North Washington Corridor: vacant farmland, several farm homes.

- South Thornton URA: far ranging web of commercial properties.

- Belmar URA, Lakewood: former shopping mall.

- Lowry URA, Denver: former Air Force Base.

- Stapleton URA, Denver: former international airport.

- Centurra, Loveland: vacant farmland.

- Timnath URA, Timnath: original town and some vacant farmland.

- Riverfront, Littleton: various properties along the South Platte.

A clear-sighted examination of the way that Urban Renewal laws work in Colorado shows they are not being used to “eliminate slum and blight”. They are not being used to fight disease and crime. Municipalities are using the façade of those worthy causes to gain access to the power of condemnation and divert taxes from their sister governments and all the taxpayers of Colorado.

The “But For” Argument

The second empty promise is that development would not have occurred except for the URA bringing that development itself. This is the “but for” argument. The Timnath URA, at I-25 and Harmony near Fort Collins, is a clear demonstration of the overstatement of that claim6. Timnath was a small town on the Burlington Northern rail line in the valley of the Cache de Poudre River. In 2005 the town formed a URA which included all of the original town and some vacant farmland, which Timnath had annexed. By 2007 discussions were underway with Walmart and a new Supercenter opened in April of 2009. Walmart had desired another location in the Fort Collins area market. Their desire was independent of Timnath forming a URA. Had Timnath not had the site available as a URA, Walmart would have picked another, more expensive site or paid more of the site impact costs at the current site. Timnath’s URA only brought Walmart to their site, it did not bring Walmart to the Fort Collins area. Walmart’s choice of sites was based on total costs for an acceptable location. It was immaterial to Walmart whether the owner of the site lowered his land price, so a URA stepped up to pay site development costs and, as a result, the permit issuing authority lowered it requirements.

This reality of a URA bringing a business to their specific site rather than to the general area is again demonstrated when Costco chose their Timnath site. The membership warehouse, Costco, has shown, by its location choices in the Colorado market, how it views URAs and TIFs. Costco has systematically chosen locations in Colorado based on serving their customer base. Costco’s experience has shown their members to be loyal and ready to travel a greater distance to a store than will a typical retail shopper. Costco chose access to highways, but whether the site stands alone or has lots of neighboring businesses seems to be hardly of any concern. When Costco chose a location in northern Colorado there were more than half a dozen qualified sites along the I-25 corridor. The sites ranged from southern locations around I-25 and US 34 and extended north beyond Fort Collins. The Timnath site was chosen because of the financial arrangements and the accommodations the City of Timnath was willing to make with Costco. So the Timnath URA did not pull a business to the area, it only pulled a business planning to come to the area to that specific site.

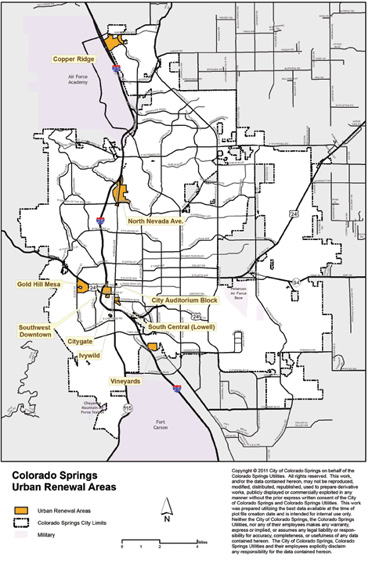

Another example of the overstated power of URAs bringing development to an area is illustrated with Costco in Colorado Springs. As Costco made their entry into Colorado Springs, they felt they needed two sites to adequately serve their membership. One site was chosen in the North Nevada Avenue URA (map 4) but the second was chosen in east Colorado Springs without URA incentives.

More disturbing, however, and lending evidence of the opposite effect is the study by economists Richard F. Dye and David E. Merriman, “The Effects of Tax Increment Financing of Economic Development”. The study examined property value growth rates for 235 northeastern Illinois municipalities, where about 1/3 of those municipalities had adapted the use of TIF. After controlling for sample-selection bias (cities that were already growing and TIF was introduced to capture a property tax-base vs. cities that introduced TIF in an attempt to spur economic growth) they found evidence to show that not only do TIF areas grow at the expense of non-TIF areas, but that municipalities that adopt TIF actually grow more slowly than those that do not.7

Among Dye and Merriman’s conclusions:

If the use of tax increment financing spurs economic development that would not have happened but for the public expenditures, we would expect (after controlling for other growth determinants and for self-selection) a positive relationship between TIF adoption and growth. If the use of tax increment financing merely moves capital around within a municipality, relocating improvements from non-TIF areas of the town to within TIF district borders without changing the productivity of that capital, we would expect (after appropriate controls) to find a zero relationship between TIF adoption and growth. What we find, however, is a negative relationship between TIF adoption and growth. This is consistent with the hypothesis that government subsidies reallocate property improvements in such a way that capital is less productive in its new location.

URAs Spur Follow-On Economic Development

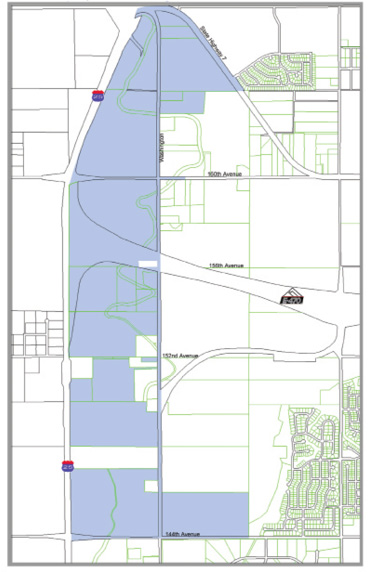

The third empty promise is that URAs initiate follow-on development and reinvigoration outside the URA. The North Washington Corridor URA, home of the Larkridge Center in Thornton provides the example. In September 2003 the City of Thornton formed the North Washington Corridor Urban Renewal Area (map 1). It was area of mostly vacant farmland ½ mile wide (between Washington Street and I-25) and about 3 miles long (144th Avenue to 168th Avenue). The Larkridge Shopping Center was built at the north end of the property. After the original building, almost no other building has occurred. The southernmost 2 miles of the property has not been touched at all. It has lain vacant for over 12 years. Finished lots, ready to build, around the originally built shopping center have also languished, have been neglected and undesired. The original buildings and tenants that moved into their locations in 2004 have had only a handful of new businesses join them.

The North Washington Corridor Urban Renewal Area sits on the east side of I-25, across from the North Huron Urban Renewal Area of Westminster (map 2). Two URAs should be reinforcing and multiplying the synergy of URA drawing power for follow-on development. That has not been the case. The boom or bust cycles of the national economy has been far more impactful on these sites.

While North Huron has been more successful, the majority of both URAs remain undeveloped, unused and unwanted. The time period these properties were ready for development includes the three years before the last downturn but also the entire recovery since 2009. The proof of the inability for URAs to act as a catalyst for subsequent activity is shown by the only development that has subsequently occurred on the Thornton side. In 2012, Thornton formed another URA immediately south of the North Washington Corridor URA, the 144th and I-25 URA (map 3). This example demonstrates that URAs can add to the underlying patterns in the US economy, but URAs cannot and do not provide enough money to move development against the business cycle, nor can they compete against newer URAs.

In Colorado Springs the North Nevada URA was begun in 2007 (map 4). The national business cycle downturn had a profound effect on development in the URA. Regardless of all the efforts directed toward continuing development, building ground to a halt. Incentives could not reverse the effects of the national economy. Without building improvements and without retails sales, there were not enough tax increments to service the bonds. The bonds for North Nevada went into default. As the national economy began to recover, development and building began anew. Without an initial, critical mass of development on which the property tax increment is paid, the URA could not meet the obligation to pay the bonds holders. Beginning in 2011, as the US economy regained vigor, building once again returned to the URA and met the point where the URA could meet its financial obligations.

Fire Chief Don Lombardi, of the West Metro Fire Protection District, worries about the harm that TIF may cause to non-TIF areas. He cited a Ball State University Center for Business and Economic Research study, “Some Economic Effects of Tax Increment Financing in Indiana” which finds that TIF areas have a negative impact on non-TIF areas8.

The Chief is not alone in that concern. In September of 1987 the City of Westminster formed a URA which rebuilt part of an older commercial area in Westminster (map 2 – South Westminster Phase I). The URA failed to stimulate economic growth in the areas adjacent to the URA. In 1996 a new URA was formed in the areas to the south of the new, rebuilt area. The second URA (map 2 -South Westminster Phase II) has failed to meet their financial obligations and the outstanding bonds were purchased by the City of Westminster in order to avoid a default on the bonds. The lesson to be learned is that instead being a catalyst that ignited growth in the larger area, the original URA did nothing to halt the slide of the neighboring areas.

Tony Robinson and Chris Nevitt, with co-authors, found in their 2005 study of Urban Renewal Areas in Denver that instead of URAs and TIF strengthening areas to stand on their own, the trend was an increasing demand for more projects.9

In Littleton, the 1980s Riverfront URA turned into a mess and an economic loss. The project failed to stimulate any growth around the URA and the project never grew enough revenues to pay the bonds for the project. The result was reported as a $9 million loss for taxpayers.10

Contrast Riverfront to Cinderella City, just a few miles north on Santa Fe Boulevard. In Englewood, the Cinderella City Shopping Mall, at one time the largest covered shopping center between Chicago and Los Angeles, was a legend and drew customers from the region. The land, which had been a city park, was purchased by the original developer from the City of Englewood. The developer wrestled with construction challenges arising from the fact that the property was a former land fill. There were no incentives, no revenue sharing, and no tax increment financing. It lived a full life: opened 1968, closed 1997. Englewood then reinvented the property, but did not use a URA. Englewood did not shift redevelopment costs to any sister government. Rather, Englewood aggressively marketed the property, found excitement and synergy in a community of users, and self-financed the balance.

Instead of being a catalyst that ignites growth, URAs have placed in developers’ minds the expectation of incentives. More precisely, URAs give public money to favored developers, and developers line up to get a piece of the action. A clear example of how expectations have grown is illustrated by Walmart locations in the Front Range. In the late 1990s Walmart completed a deal for a location at the old Cinderella City that was not developed as a URA and no TIF money was available. Walmart paid a market price for their property to be part of the Englewood Transit Oriented Development. But in 2004 when TIF money was available, Walmart’s developer of the South Sheridan Urban Renewal Area in Westminster negotiated and was given more than $5 million dollars of public money. Walmart received the benefit of public money for the Timnath URA location (opened 2009).

It is instructive to note that Walmart still has an option on the property in the boundaries of the abolished-by-voters URA in Windsor, Colorado. Without the incentive of public money there has been nothing built. Walmart must view the land as very valuable because the land is unavailable to any other developer for any similar purpose or any alternate users.

Untold Cost of URAs/TIF

Picture taken from 160th and I-25 looking northeast. Vacant lots of the North Washington Corridor in the foreground with the Larkridge shopping center in the distance. November 2015, 12 years after the formation of the URA. Photo by Bruce Baker.

It’s about the money. Every government, at every level, is protective about their revenue sources, and rightly so. The Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR) has wrought foundational changes to the way Colorado governments approach projects, taxes and taxing. The requirement that voters must approve all tax increases achieved one of its desired effects by making governments very reluctant to bring tax increases to a vote by the people. The old style of only having to convince the members of a governing body of the necessity of a tax increase has been transformed into bringing a marketing campaign to citizens. This has constrained the options governing bodies feel they have available. The financial tool TIF, enabled by the declaration of URAs, has given municipal governing bodies an alternative to placing a tax increase request before the voters. Municipalities have viewed TIF and URAs as a way to reclaim some of the prerogatives they felt they lost to TABOR.

The prerogatives and freedom of action that municipalities feel they have reclaimed by using URAs and TIF has a large cost to their sister governments. There is no such thing as free money. Every dollar of taxes, especially in the TABOR environment, is anticipated and allocated by the government under which the taxes are levied. A reduction in the anticipated flow of a government’s revenue is a very large burden for any district to carry. When that reduction is coupled with increased demands for services directly caused by development, the burden grows. This is why the diversion of one government’s taxes to another government becomes so contentious and destructive. TIF function by diverting the tax revenue stream of one government entity into the pocket of another government entity. The losing entities are county governments, special districts, school districts, and the State of Colorado. This harm caused to sister governments is why URAs are intended to be used only when a serious threat to both the municipality and people of Colorado exists.

Picture taken from 160th and I-25 looking southeast. Vacant lots extend for 2 miles south to 144th in the North Washington Corridor URA. November 2015, 12 years after formation of the URA. Photo by Bruce Baker.

The TABOR environment has had another profound effect on governments at every level. TABOR allows governments to automatically grow their taxes and spending by two objective measures: inflation increase, and growth. The benefits of growth are now viewed with equal consideration as is the cost of growth. If a district grows, it can both tax more and spend more.

Special Districts Pay:

The experience of The West Metro Fire Protection District serves as an example of how special districts are hurt by URAs and TIFs. Chief Don Lombardi of the West Metro Fire Protection District (located in the west and southwest suburbs of Denver in Jefferson County) has had to deal, first hand, with the effect of tax diversion by URAs. Besides losing their proportional expected share of revenue increase from development along Colfax Avenue, the City of Lakewood’s URA at the former Villa Italia Mall caused a reduction in the full increment of development revenue increases from that site. Since then, West Metro has been able to work with Lakewood’s URAs and they have made arrangements less detrimental to the district. The URA still controls the process, instead of using the old mall assessment as a base value, Lakewood reduced the site’s value to dirt, thereby increasing the size of the increment available to the URA and reducing the share for West Metro. Adding burden to the losses, the new Belmar development includes a significant amount of housing and corresponding increase in service demands to the fire protection district.

Most special districts are heavily dependent on property taxes. The increment increases in property taxes are entirely diverted by URAs unless sharing agreements have been hammered out with the URAs. To address the loss of revenues and increase in demand for services, West Metro Fire asked the voters for a mill levy increase. The voters turned the mill levy increase down11. It is understandable how voters, frustrated with what they consider to be government excess and waste, took an opportunity presented to strike down a tax increase by one government entity, when it was the actions of a separate, culprit government entity that drove that tax increase request. Reductions were planned to address the realities that West Metro faced. The loss of property tax revenue impacts these districts for 25 years. The story played out in West Metro is the nightmare scenario of most special districts.

Counties Pay:

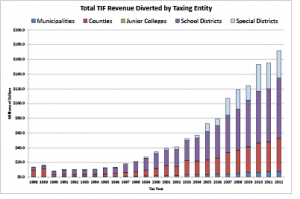

Counties lose the entire amount of property tax increment increase for the life of the URA, usually 25 years. Counties provide many of the services that are directly increased by development: jails, courts, roads, social and human services. The services that counties provide are some of the most expensive that any level of government provides. As is the case with special districts, the loss of property tax revenue increment has been the fundamental objection by counties to URAs. In 2015, during the second attempt at the Colorado Legislature to reform URA laws, Colorado Counties, Inc. published the graph on the next page that illustrates the amount of diverted revenue and the direction that URA/TIF use was trending.

Used with permission of Colorado Counties, Inc. Updated by Larimer County Budget Office 8/21/13

Another major complaint voiced by counties is the way the municipalities remove their sales tax increase increment from the revenue streams that pay the TIF bonds. They voiced this complaint in their appeal for the passage of HB 1348 in 201512. An example of this shifting of the burden for repayment from a mix of both property tax increment and sales tax increment can be found in the actions of the City of Westminster in the North Huron Urban Renewal Area.13 As the City of Westminster states:

The sales tax pledge has been 0% since March 2010 as funds on deposit with Compass Bank along with anticipated property tax increment are sufficient to meet debt service requirements. Therefore, the City now retains all sales tax revenue received from this URA, which are used for City operations.

When the bonds were established the sales tax increment was pledged for bond repayments. If the increment from the sales tax had continued to be used for bond repayment, the result would mean the continued loss of county property tax would end sooner than the 25 year TIF period.

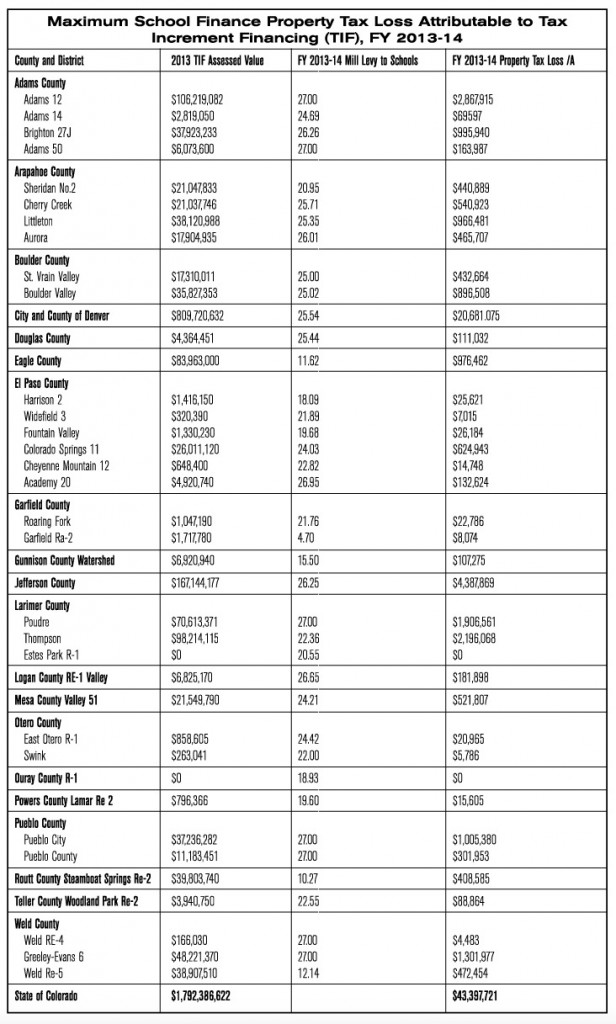

Schools and the State of Colorado Pay:

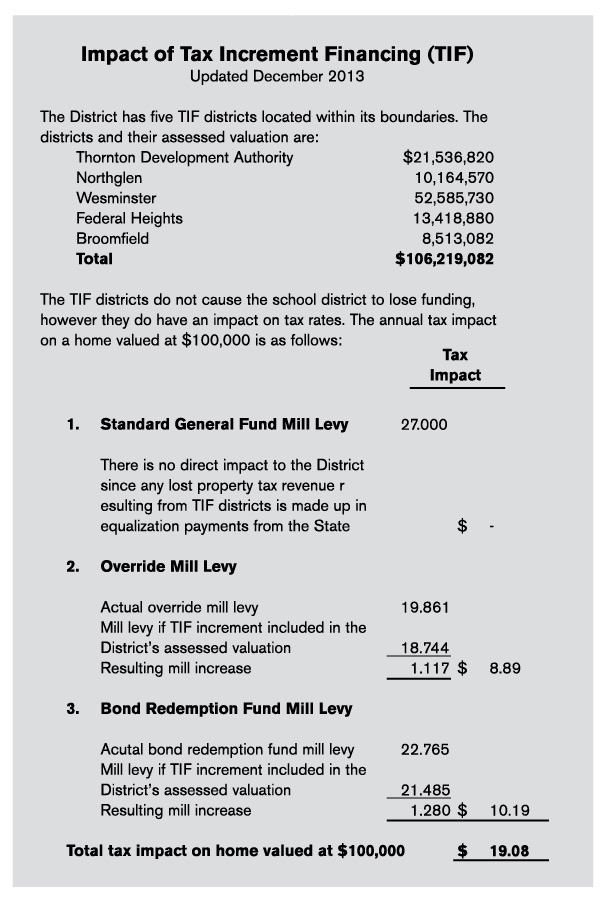

While counties and special districts are the second and third largest source of property tax increment diverted into the URAs, the largest source is property tax that would have flowed to the school districts. This loss of tax money would be devastating to the school districts without a mechanism to replace it. Proponents of URAs and TIFs refer to “backfill” as the replacement of lost revenue. Examination of the “backfill” reveals that the money diverted from schools comes from two sources. The first source is an up to 27 mills replacement from state taxpayers. The second source is a quietly imposed mill levy increase on all district tax payers, done without the vote required by TABOR.

The Adams 12 Five Star School District is a suburban school district in the northern suburbs of Denver, located in Adams County and serving portions of the cities of Thornton, Westminster, Broomfield, Northglenn and Federal Heights. In Table 2 (page 23), the district shows that state government replaces 27 mills of diverted money. The remaining missing money is gained by increasing the mill levy on all taxpayers within the district. This resulted in a 2.397 mill levy increase. It is part of the reason that Adams 12 has the highest school tax in Colorado. The only available mechanism to replace the money lost to municipalities is a tax increase vote. Similar to the West Metro Fire Protection District, the last mill levy increase presented to the voters in Adams 12 was defeated. Another dimension of inequity forced upon the State by the school “backfill” system is how the backfill flows in large measure to rich districts, most glaringly, Denver. Denver accounts for about 1/7th of Colorado’s population and about 1/10th of the public school students. But Denver has consistently taken nearly 1/2 of the State URA backfill money (Table 1) to schools.

Further compounding the inequity, Denver has an assessed value per pupil of over $146,000. Compare this to the vast majority of school districts that run between a low in Aurora 28J, Adams 12, and Brighton 27J in the $50,000s, and Jefferson R1, Poudre R1, and Littleton in the $80,000s. This means the school district that is most financially able to adsorb the portion of revenue replacement also has the smallest proportional burden for their district taxpayers to shoulder.

Drilling down into the state backfill data (Table 2) a very revealing pattern is shown. Denver is not alone as a wealthy area having no reluctance or reservations to access state funds. With 899,112 students in Colorado and a net assessed value of $102,988,962,195 the average net assessed property value per student is about $114,500 per student. While Denver at $146,941 runs nearly 30% above the State average, Boulder at $187,293 runs 60% above, Steamboat Springs at $320,423 is 180% above and Eagle at $401,922 runs 3 and ½ times the state average of net assessed property per student. It is impossible to reconcile these numbers with the legislative intent of Urban Renewal Laws to address the serious and growing menace that slums and blighted areas cause the State.

In an October 20, 2013 Denver Post article by Jeremy Meyer14, the Denver school tax diversion is explored. Denver City Councilman Paul Lopez spoke against the diversion of school taxes and was the sole vote to oppose the continuing diversion of school tax. The Councilman’s allegations were corroborated by Denver Public Schools Chief Operations Officer David Suppes. The defense of the practice was that “redevelopment will bring back much more tax money than if redevelopment would never have happened.” Officials also pointed out that sales tax revenues had increased from $25 million in 2006 to $37.5 million in 2012. The official forgot to mention that no sales tax is collected by the school district.

The net effect of the school “backfill” system is to funnel tax money from all Colorado taxpayers to replace money diverted into the hands of municipalities that are clearly and brazenly misusing the URA requirement of fighting statewide threats of disease and crime. Most URAs are economic development projects, luring ready developers to specific sites and the most generous deals. Instead of solving statewide problems, URAs are encouraging battles between municipalities.

Both state and local taxpayers are the losers in this battle. The unintended consequence of the “backfill” system flies in the face of the intent of the mechanisms in the school funding equalization system.

Everyone Pays:

There is one additional untold cost of URAs and TIFs. In theory, URAs replace like for like. The underlying assumption is that the reconfigured area will need services identical to, or less than, the old area. As the legislature declares in the URA law, a slum demands more, and costlier services than does a desirable neighborhood. An old, run-down, undesirable slum of 1,000 residences is replaced by a desirable new neighborhood of 1,000 residences. The new neighborhood pays twice the taxes, and the increase (or new increment) in taxes pays the bonds that built infrastructure for the new neighborhood. This means the local government collects the same level of revenue paid by the old neighborhood, but from a new one that demands fewer services.

This is a theoretical double-win for municipalities. Win number one is a new, desirable neighborhood with upgrades paid by the residents through increased tax collections. Win number two is fewer and less costly services to the new neighborhood.

The theory is not the reality. The overwhelming majority of URAs in Colorado have been economic development projects. They have significantly increased demand on public infrastructure, without paying for increased capacity of that infrastructure. It is the same situation that opponents of suburban sprawl claim. The impact on infrastructure needs is not compensated to the providers of those needs. In already congested areas, URAs are clearly not compensating providers of infrastructure according to their needs.

A good example is a large suburban housing development built beyond the city limits. A connecting road, which had been adequate for decades, is now dangerously crowded and must be expanded to meet the demands of safety. This has been the same situation with URAs. URAs are placed inside of municipalities and in many places where infrastructure is operating at or above design capacity. The cost impact for bringing city infrastructure up to safety minimums is an order of magnitude higher than in the suburban sprawl scenario.

Denver is, again, the worst offender in this situation. The Denver population grew from 554,636 in 2000 to an estimated 663,862 in 2014. Denver has placed more residences, people, and destinations into their city limits partially through their use of URAs. These new people and destinations have increased the users on the street and interstate network. However, Denver has not built new roads or increased the capacity of existing roads to serve the new people in their city. Denver has pushed the cost for increased capacity in infrastructure onto state and federal taxpayers. The options of expanding I-25 thru Denver are non-existent. The cost for building a new I-25 thru Denver Metro would be staggering. I-70 is in the same, over-capacity situation as are many other streets in Denver. Ask any Denver resident about the traffic situation at Colorado Boulevard and Alameda.

This doesn’t mean Denver taxpayers are avoiding all the burden of these increased costs, both in financial terms and societal goals. Robinson and Nevitt identify many of the costs Denver taxpayers must bear. Because data and calculations are permanently hidden from the public and elected officials, there is no way of holding TIF projects accountable. They note that “Denver’s private developer partners are demanding greater than average returns on TIF projects,” thus giving connected partners inflated profits and creating unfair advantages in the marketplace. They further note that “TIF-projects create service needs they don’t pay for.” So the shortfall must be covered by other taxpayers.

Source – excerpted from Memorandum from Greg Sobetski, 303-866-4105, dated April 25, 2014, Colorado Legislative Council Staff

A Government Planned Future, the Westminster Example

Which one of the pictures below is an Urban Renewal Area in Westminster? It was part of a development that stalled. It has lain dormant for years. The City holds all the debt for the URA district but cannot entice any builder to complete the project. The other picture is of a development that stalled and, has struggled through a series of owners, but has not been given public money to address the situation. Where is the difference that required public money? This is public money that comes not only from Westminster, but from all Colorado taxpayers.

Photo by Bruce Baker.

Photo by Bruce Baker.

It is the authors’ contention that elected officials in Westminster have chosen to become central planners, using the resources of the public to paint their vision of the future. They are not alone among Colorado officials in using public money to make their private visons come to life. If they were only using City money, the concern is only that of City voters. But Westminster leaders and city planners have used URA and TIF, which is the money of sister governments and state taxpayers, to bend the market to make choices those planners want. The choices produced are not necessarily what consumers want. This same pattern has come to life in Lakewood’s Belmar and Denver’s Stapleton.

Westminster’s “New Downtown”

The current paradigm in urban planning is higher density housing and under-building infrastructure such as parking for cars. Instead of being inclusive and allowing these concepts and designs to participate in the market, Westminster is mandating these concepts and designs as the controlling paradigm at our New Downtown. By using URAs and TIFs, Westminster has access to tens of millions of dollars without the extra work of following TABOR. If the national economy stays strong and ready partners buy a place in the project, followed by retailers, office users, and apartment dwellers who see the rental units as desirable, then the New Downtown will prosper. Failure in any of those components means the responsibility will fall upon the taxpayers of Westminster to pay for this project.

The New Downtown is being built on the 105 acres that from 1977 to 2009 was the Westminster Mall. The Westminster Mall was a destination mall and the cash cow of sales tax for Westminster. In 1999 the mall produced peak sales tax revenues for the city. In 2001, during the recession, with the demise of Montgomery Ward and in anticipation of the Flatirons Mall being built just 7 miles away, the City approached the mall owner in order to build a partnership that would serve the interests of both parties. In the end the owner did not share the vision and values of the city planners. With the demise of major anchors and the opening of the Flatirons competitor there was a steady decline in business at the mall, and City relations with owner became more difficult. City planners began to form a vision on their own that would completely transform the property into a New Downtown. The vision included residential neighborhoods, theaters, a restaurant walk and other amenities.15 The decline of the mall became an opportunity for City leaders and city planners to advance their own dreams.

In 2009 the Westminster City Council contorted the legislature’s definition of slum and blight and declared the mall a “blighted” area. The city formed a URA. Negotiations with the owner slipped from difficult to hostile and ended up in the courts.

In 2011, the city spent $22 million dollars to buy the last major remaining portion of the mall, appraised for $17 million dollars, from the heirs of the old owner. It was a startling price for the property which the City had declared in 2009 to be “blighted”. In total the City has spent nearly $30 million in assembling the site. In view of the price paid for the mall, it is doubtful if the property was ever viewed as “blighted” by the market place.

From 2011 to 2013 Westminster participated in discussions with three different master developers. No agreement with any of the developers was reached. The City’s vision was very specific and allowed for little change. In 2013 the design firm of Torti Gallas and Partners further refined the vision of the city planners. In 2014 another master developer worked with the city and again no common vision could be found.

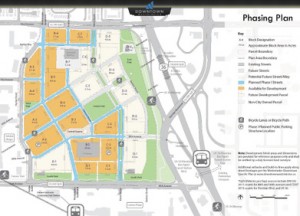

In 2015, using the anticipated revenue stream of diverted TIF property taxes, the City undertook $40 million of debt, used $10 million in cash and $15 million from projected property sales of ½ of the site, to commence building the New Downtown. This additional money brings the total of public money to over $100 million dollars. The $65 million new dollars will be used to begin building the roads, sewers, water system, sidewalks, parks, plazas and two structured parking garages for the New Downtown. Except for parks, these types of costs are typically costs borne by the developer, built to city requirements and are given to the city at no charge.

The walkable blocks in the pedestrian friendly environment will have 4 and 5 story buildings with first floor retail spaces and offices or residences above. Except for a few street parked cars, all cars will be hidden away in inconvenient, structured parking garages. There may be some owner occupied townhomes, but the rest of the site will be rentals with special

consideration given to affordable/workforce (subsidized) housing. The plans include 4,500 new residents. However, our plans do not include any public buildings or schools, nor churches, or temples, or reading rooms. It is an ambitious plan that was never meant to “eliminate slum and blight”, though Westminster pretended to have that goal.

The irony in the situation is that Westminster may be building a slum of the future. There will be 4,500 people living in 2,300 residences, of between 500 and 1600 square feet. Only a couple hundred units will be owner occupied and balance of residences will be controlled by a handful of major landlords. This living situation sounds more like the crowded inner-city slum of 100 years ago than to a downtown of the Future. Added to the “vibrant, day-and-night activity” are 8,000 new workers arriving daily at the site, which has limited parking and bus service. How many daily shoppers will be required to support the 700,000 square feet of park-in-the-garage retail?

Block B-7 is not part of the plan. It sits in the middle of Fenton Street blocking the road connection.

Four master developers in private enterprise were invited to make this bold investment. They declined. One hundred million dollars of public money is at risk. The $40 million Certificates of Participation (COP) debt will be serviced by diverted property taxes and is a total loss to Jefferson County and state taxpayers. The over $60 million of Westminster tax dollars has no defined pay back schedule. If the project becomes a runaway success, there is no plan to share the profit with the City as an investor. The project is repeatedly referred to as “community building”.

Note that the bullet train icon says “future” rail station. The Regional Transportation District (RTD) has extended the expected date of service. The old date of 2042 was thought to be too soon.

But who are we building this community to serve? It appears the City is building a bicycle and pedestrian friendly, day-and-night active, restaurant and entertainment filled, government planned utopia for “20-somethings”. The New Downtown will be welcoming to the physically fit and those with discretionary dollars. How is this New Downtown welcoming to a lower-income family with 3 kids in tow, or the physically challenged or senior citizens?

None of these arguments should be happening in Westminster. City government should be a neutral referee on a level playing field for free market entrepreneurs to compete. Maybe the future lies in a physically fit, forever-young demographic of singles. Advocates of that future should take the risk in building that future. Westminster should not be spending property taxes diverted from Jefferson County and Colorado taxpayers to make city planners’ dreams a reality. Without diverting tax dollars from sister governments, Westminster could not advance this “vision” of the future.

Enabled by TIF, this is what government planning has become. Socialized risk, and private potential profit for a connected few. All this spending of taxpayer money is justified by invoking the excuse of fighting disease, crime, substandard housing and “blight”. And, of course, no one ever lived at the old Westminster Mall.

When those at the helm of government cannot or will not restrain themselves, it is time for the rule of law, through legislation or the ballot box, to withdraw the discretion and power being abused.

Citizen Pushback on TIF/URA

The judgment that municipalities are misusing URA law is not only made by sister governments having their property tax diverted or whistleblowers or tax crusaders. When the voting public has entered into the process, they have rejected URAs and TIF.

The Littleton Example:

In a special election on March 3, 2015, Littleton voters overwhelmingly (60-40) approved Initiative 300, citizen-led ballot measure that requires voter approval for any urban renewal plan that utilizes TIF financing.16 Opponents of 300 argued that if a URA couldn’t hand out TIF financing packages as they saw fit, no one would be willing to develop projects in that Denver-metro area of 44,000 residents. As the Littleton Independent newspaper editorialized at the time, “Just sending Initiative 300 to a vote of the people hurts Littleton’s image of being pro-business and a good place in which to invest.”17

Yet at the April 5, 2016 Littleton City Council meeting, more than a year after passage of 300, city staff reported that Littleton’s planning and development department is “swamped.”18

The Wheat Ridge Example:

In the November 2015 election, voters in Wheat Ridge passed their own Initiative 300 as a charter amendment, stripping their URA board of TIF, cost sharing, and revenue sharing discretion. Under the ordinance, any TIF over $2.5 million must now be approved by voters at the ballot. TIFs under $2.5 million must be approved by Wheat Ridge City Council, rather than by the unelected URA board members.19 Wheat Ridge 300 was made retroactive to include an existing TIF agreement between the Wheat Ridge Urban Renewal Authority and a developer. Predictably, the developer sued over the measure, saying among other things that the retroactivity created an ex post facto (or after the fact) law, and thus violates the Colorado Constitution. In June 2016, Jefferson County District Court granted summary judgement to the developer on the ex post facto claim, noting that “…the facts establish unconstitutional retrospectivity of Ballot Question 300 solely as it pertains to the Agreement and TIF.”

Wheat Ridge for its part remained neutral on the ex post facto claim – meaning the city simply didn’t defend that part of the charter amendment.

Make no mistake, both the city, and the developer, wanted their TIF. In the meantime the rest of Measure 300–the requirement for either voter or city council approval of new TIFs– stands, at least as of publication of this study.

The Windsor Example:

In 2007 the Town Board of Windsor jumped into the URA arena and set URA boundaries that included the main street and a proposed site for a Walmart. In response, Windsor voters, encouraged by a local Fire District, abolished the URA by a margin of 60% to 40%.20 In response, Windsor in 2011 formed a Downtown Development Authority (DDA) through a vote of downtown business and property owners, funded through a sales tax increment from within the boundaries of the DDA. There are alternatives to abusing urban renewal, and obligating taxing entities and their tax payers from outside the URA, for development.

The Steamboat Springs Example:

In early 2015, the Steamboat Springs City Council voted to declare its tourist-destination downtown as “blighted.” The blight designation was a necessary first step in a plan to form a downtown URA and utilize TIF for redevelopment projects. This prompted a groundswell of both public and sister governments comments. For example, Steamboat Springs Board of Education member Scott Bideau wrote that:

“Steamboat’s existing, TIF-funded mountain URA currently diverts over $400,000 per year in local property tax revenue away from the school district while also increasing property taxes outside the URA to cover the school mill levy overrides and bond payments that are not paid for by new development within the URA or backfilled by the state.”21

In addition, Steamboat citizens started the process for a petition drive to require voter approval for URAs/TIFs modeled after the Littleton 300 measure.

In June 2015, the Steamboat Springs City Council acquiesced to public sentiment and voted to kill the URA/TIF plan they had approved only months before.22

While Colorado ski-towns such as Steamboat Springs were impacted by the economic recession in 2008-09, The Denver Post reported in July 2016 that:

“Resort towns such as Aspen, Vail, Breckenridge, Crested Butte, Telluride, Winter Park and Steamboat Springs enjoyed a robust rebound in 2013-14 and 2014-15 with in-town spending and sales tax collections reaching highs. The record-setting continued in 2015-16, with sales tax revenues reaching highest-ever levels for nearly every ski community in the state.”23

Hardly an indicator of a community in need of urban renewal and TIF.

The Estes Park Example:

In a January 2010 special election, Estes Park voters overwhelmingly (61-39) abolished the city’s urban renewal authority. The formation of new URAs in Estes Park now requires a popular vote.24

From 2010 to 2015, Estes Park’s town lodging tax receipts went from just over $1.7 million to just under $3 million (excluding a new 1% tax increase) and town sales tax receipts went from just over $7 million to just over $12 million (again, excluding a new 1% tax increase).25

Estes Park appears to be enjoying economic growth without a URA.

Recent Legislative Efforts on URA/TIF

In 2014 the Legislature passed House Bill 137526, to address the inequities in Colorado Urban Renewal Law, but Governor Hickenlooper vetoed the bill. In 2015 the Legislature passed another try at addressing the ongoing inequities, and House Bill 134827 became law. The major element of the bill requires the inclusion of representatives of taxing entities within the boundaries of the URA, including county governments, school districts and special districts, as members of the URA’s governing body, thus giving those taxing entities greater say as to whether their tax revenues can be dedicated to TIF.

In 2016, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 177, making modest technical modifications to the 2015 legislation with regard to allocation of tax revenues by taxing entities within a URA.

The impact on urban renewal of these new laws is still in a state of flux. There will be a reassessment of the use of URAs and TIF. Municipalities are lamenting the forced negotiations they must have with sister governments before moving URAs ahead. They also realize that the bonanza of keeping their sales tax increases out of the overall TIF repayment system will eventually be on the negotiating table. The Legislature is essentially hashing out turf battles between municipalities and other taxing entities within URAs.

CONCLUSION

A more fundamental reassessment is needed. Municipalities have been far too provincial in their view of URAs and TIFs. In their rush to protect their turf and resources, they have overlooked the far more meaningful inequity in the system. Denver is the primary beneficiary of URAs and TIF. Except for a few ski towns and Boulder, Denver is the wealthiest municipality in Colorado. Denver uses URAs and TIF to benefit itself and its connected business partners. The draining of state resources by Denver, harms every taxpayer in the state.

Any reassessment must also include the ethical dimension of urban renewal and tax increment financing. There are no slums in Colorado. There is no free money in Colorado. Urban renewal long ago ceased being a legitimate tool for addressing the slum, blight, disease, and crime of urban decay. Instead, it is today used almost exclusively as an economic development incentive that allows politicians and planners to offer public subsidies to private interests for preferred economic development projects, in direct conflict with the legislative intent of Colorado’s urban renewal law. To keep in place mechanisms that drain voter approved revenues from one independent government unit to another independent government unit without a clear, compelling, and overwhelming reason is wrong.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Repeal TIF Authority Altogether:

The Colorado Legislature should abolish the TIF authority for URAs. There are no slums and blighted areas anywhere in Colorado that pose a serious and growing menace to municipalities, or the State as a whole, and are injurious to the public health, safety, morals and welfare of the people. California invented TIF in 1952 to help rebuild blighted neighborhoods through redevelopment agencies (RDAs). Much like Colorado, TIF in California evolved in a mechanism for doling out public subsidies to crony interests and an easy way for cities to increase their budgets at the expense of other agencies. TIF became such a huge burden on schools and other programs that in 2010 the California State Legislature repealed the TIF law.28 The Legislature authorized URAs and TIF as a matter of statewide interest. Thus the Legislature could declare victory over slum and blight and repeal TIF authority for URAs.

Means Test URAs and TIF:

Considering opposition from entrenched special interests that benefit from URAs and TIF, the Legislature could take an intermediate step of means testing URAs. As this paper shows, URAs and TIF overwhelmingly benefit wealthier cities at the expense of poorer cities. By specifying objective financial data (per student assessed values, per capita incomes falling below US average, negative economic growth year over year, etc) the Legislature should restrict municipalities from using URAs and TIF to chase and geographically manipulate existing economic growth in order to capture a tax increment.

Include Both Property and Sales Taxes Equitably:

In the meantime, and in response to the loss of revenue endured by sister governments, the Legislature should require both property tax increment and sales tax increment to be dedicated to the repayment of the TIF bonds. This would lessen the time that sister governments lose their share of taxes. While not mitigating the immediate losses caused by TIF, it would minimize the ability of municipalities to selectively take a bonanza of revenue increases.

Tables

Source – Correspondence with Adams 12 School District Super- intendent Chris Gdowski, dated Dec 12, 2013

Maps

Source – Thornton, Colorado Website, November 21, 2015

Source – Westminster, Colorado Website, November 21, 2015

Source – Thornton, Colorado Website, November 21 2015

Source – City of Colorado Springs Website, November 21, 2015

1 Robert K. Melton, “The Unintended Consequences of Purposive Social Action,” American Sociological Review, Volume 1, Issue 6, (Dec., 1936), 894-904. http://www.romolocapuano.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MertonUnanticipated.pdf

2 Colin Gordon, “Blighting the Way: Urban Renewal, Economic Development, and the Elusive Definition of blight,” Fordham Urban Law Journal, Volume 31, Issue 2, (2003).

3 Declaration of Policy, Housing Act of 1949, 63 Stat. 413, 42 USC Sec. 1441 (1958).

4 JA Stoloff, “A Brief History of Public Housing,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. http://reengageinc.org/research/brief_history_public_housing.pdf

5 Ted DeHaven, “HUD Scandals,” Cato Institute, Downsizing the Federal Government website, June 1, 2009. http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/hud/scandals

6 Colorado Municipal League Seminar, “Negotiating and Regulating the Development Opportunity” Breckenridge, Colorado June 17, 2015.

7 Richard F. Dye and David E. Merriman, “The Effects of Tax Increment Financing on Economic Development,” Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 47, Issue 2 (March 2000) 306-328. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119099921496

8 Dagney Faulks and Pam Quinn, “Some Economic Effect of Tax Increment Financing in Indiana,” Ball State University for Business and Economic Research, Policy Brief, Jan. 28, 2015. http://projects.cberdata.org/reports/TifEconEffects-012815.pdf

9 Tony Robinson and Chris Nevitt, “Are We Getting Our Money’s Worth? Tax-Increment Financing and Urban Redevelopment in Denver,” Front Range Economic Strategy Center (2005). http://fresc.org/wp-content/uploads/013/12/TIF-II.pdf

10 Peter Blake, ”Littleton proposal would place check on urban renewal, TIFs,” Complete Colorado, Jan. 9, 2015 http://completecolorado.com/pagetwo/2015/01/19/blake-littleton-proposal-would-place-check-on-urban-renewal-and-tifs/

11 Carlos Illescas, “West Metro Fire chief proposes cuts in service after tax hike fails,” The Denver Post, Sept. 3, 2014. http://www.denverpost.com/2014/09/03/west-metro-fire-chief-proposes-cuts-in-service-after-tax-hike-failed/

12 Colorado Counties, Inc., Special Districts of Colorado and Colorado Association of School Boards fact sheet in support of House bill 15-1348, Urban Renewal Fairness Act. http://ccionline.org/download/FSHB15-1348.pdf

13 City of Westminster staff report, Westminster Economic Development Authority 4th Quarter Financial Update, Feb. 13, 2015. http://www.ci.westminster.co.us/Portals/0/Repository/Documents/CityGovernment/Community%20Development/WEDA022315.pdf

14 Jeremy Meyer, “Does downtown Denver tax district take money from DPS?” The Denver Post, Oct. 30, 2013. http://blogs.denverpost.com/thespot/2013/10/30/does-the-downtown-denver-tax-district-take-money-away-from-dps/102130/

15 Van Meter, Williams & Pollack, LLP architects, A New Downtown for Westminster project sheet. http://www.vmwp.com/projects/westminster-retail-center-redevelopment.php

16 John Aguilar, “Littleton voters pass measure restricting city’s urban renewal powers,” The Denver Post, March 3, 2015. http://www.denverpost.com/2015/03/03/littleton-voters-pass-measure-restricting-citys-urban-renewal-powers/

17 House Editorial, “Littleton voters should say no to 300,” Littleton Independent, Feb. 18, 2015 http://littletonindependent.net/stories/Editorial-Littleton-voters-should-say-no-to-300,180931

18 Video of June 5, 2016 Littleton City Council meeting video, at mark 1:03:04. http://www.littletongov.org/connect-with-us/city-leadership/meeting-videos-documents

19 Glenn Wallace, “What a year for Wheat ridge,” Wheat Ridge Transcript, Jan. 5, 2016. http://wheatridgetranscript.com/stories/What-a-year-for-Wheat-Ridge,204907?

20 Town of Windsor Statement of Votes Cast, 2007 coordinated election, Nov, 21, 2007.

21 Scott Bideau, “Steamboat’s downtown Urban Renewal authority comes at the expense of local school,” Complete Colorado, June 5, 2015. http://completecolorado.com/pagetwo/2015/06/05/steamboats-downtown-urban-renewal-authority-comes-at-the-expense-of-local-schools/

22 Scott Franz, “Steamboat city council rejects downtown URA,” Steamboat Pilot, June 16, 2015. http://www.steamboattoday.com/news/2015/jun/16/steamboat-city-council-rejects-downtown-ura/

23 Jason Blevins, “Yet another record winter for visitor spending, sales tax harvest in Colorado ski towns,” The Denver Post, July 10, 2016 http://www.denverpost.com/2016/07/10/colorado-record-winter-visitor-spending-sales-tax-harvest/

24 Steve Porter, “Estes Park faces future with no urban renewal authority,” BizWest, Feb. 12, 2010 bizwest.com/estes-park-faces-future-with-no-urban-renewal-authority/

25 Visit Estes Park Annual Reports, 2012 and 2015. https://res-1.cloudinary.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/estespark/Counter_Map_6_15_12_ca486874-89f1-43e6-9c37-43ca3ef1c83a.pdf

26 Ed Sealover, “Hickenlooper vetoes bill limiting Colorado’s Urban renewal developments,” Denver Business Journal, June 6, 2014. http://www.steamboattoday.com/news/2014/jun/09/hickenlooper-vetoes-urban-renewal-authority-bill/

27 Hickenlooper signs urban renewal reform despite threats of stalled projects,” Denver business Journal, May 29, 2015. http://www.bizjournals.com/denver/blog/capitol_business/2015/05/hickenlooper-signs-urban-renewal-reform-despite.html

28 George Lefcoe and Charles W. Swenson “The Demise of TIF-Funded Redevelopment in California,” The Planning Report, July 24, 2014. http://www.planningreport.com/2014/07/24/demise-tif-funded-redevelopment-california

Copyright ©2016, Independence Institute

INDEPENDENCE INSTITUTE is a non-profit, non-partisan Colorado think tank. It is governed by a statewide board of trustees and holds a 501(c)(3) tax exemption from the IRS. Its public policy research focuses on economic growth, education reform, local government effectiveness, and constitutional rights.

JON CALDARA is President of the Independence Institute.

DAVID KOPEL is Research Director of the Independence Institute.

BRUCE BAKER is an elected member of the Westminster City Council.

MIKE KRAUSE is Director of the Local Colorado Project at the Independence Institute.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES on this subject can be found at: www.i2i.org.

NOTHING WRITTEN here is to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the Independence Institute or as an attempt to influence any election or legislative action.

PERMISSION TO REPRINT this paper in whole or in part is hereby granted provided full credit is given to the Independence Institute.